Newsletter – February 2025

By Matthew Cleary

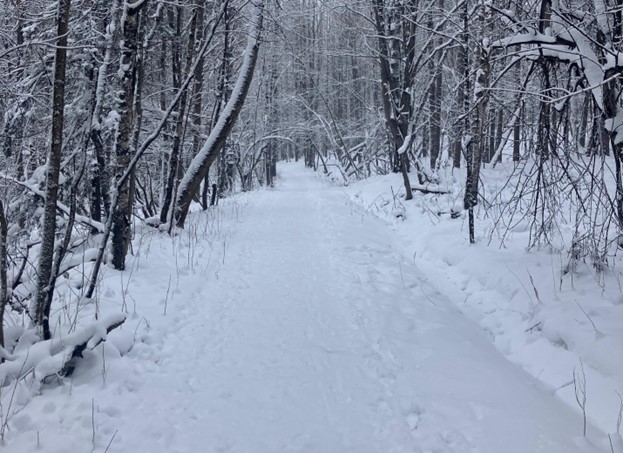

It is January and winter has set in. It is a wonderful time of year to be in the woods. The hiking trails are covered with ice and snow. It crunches and squeaks under your boots if you walk on very cold days. There are hardly any smells in the air or colors in the landscape besides shades of gray, and there are no bugs. If you take a hike while light, fluffy snow is falling, the muffled intimacy can give the impression that you are alone in the forest, and if you stop moving everything goes quiet. The snow covering everything can give the impression that there are no sharp edges or hard surfaces. A few chickadees or a woodpecker in the distance might break the silence. A squirrel or a deer might materialize. By and large, though, the forest seems to be in hibernation.

Many of its animals are as well, or at least some form of it. An extreme example of this is the wood frog. In spring, summer, and fall, they are everywhere in the forests around Lake Massawippi. While working on the hiking trails we can sometimes see ten or fifteen a day if we are working near water. Through the winter they stay. Their bodies freeze. A frog’s heart and lungs stop functioning. They remain in a state of suspended animation for months until Spring arrives, when they thaw and come back to life.1

Many other animals reduce their activity as a means to conserve energy as well. Groundhogs hibernate, spending the winter in a deep sleep. Others like bears, chipmunks, and skunks enter a state called torpor. Torpor is a general term for a state of inactivity during which animals enter a deeper sleep that allows for energy conservation by slowing metabolic rates and decreasing body temperature slightly.2 Their breathing slows and their heart rate drops just like truly hibernating species, but their body temperature drops only by a few degrees and their brains stay active.3

From migrating butterflies and birds, to insects that pass the winter as eggs, or larvae, or nymphs, the animals that seem so abundant along the trails in summer have adapted to the cold of winter. Their lifecycles depend on it. They need the change of seasons to be born, to eat and grow, to thrive and to reproduce.

We are not so different in our need for seasonal change. I lived several years in Southern California where there were no real seasons to speak of, where every day was sunny and warm and, for the most part, always the same. It was like living in the movie Groundhog Day, where the same day repeats itself. It became hard to keep track of the passage of time, to remember if something happened last week or last month, four months ago or four years. Aside from missing the hot topic of discussion that is the weather, not experiencing the rhythm of seasonal change creates a disconnect between our lives of that of the natural world around us.

One of the benefits I’ve found of working outside in Quebec is the opportunity to experience the seasons changing slowly. We begin work on the trails each spring when the sun melts the snow and ice, and everything smells like mud and decay and new life. We get sunburned at first before the leaves comes out. Ferns start to unfurl, and wild garlic is at its best. Then black flies appear, then mosquitoes and birds and everything else.

On May 15th of last year, I made a recording during my lunch break using the Merlin Bird ID application on my phone and recorded the songs of 11 different bird species. This was in just one spot on the Pic de Wippi trail. There are so few warm months here. Everything grows fast. It changes by the day. Before long the leaves form a dense canopy, and the air remains heavy with heat and humidity. It is a cacophony of birds and insects.

On May 15th of last year, I made a recording during my lunch break using the Merlin Bird ID application on my phone and recorded the songs of 11 different bird species. This was in just one spot on the Pic de Wippi trail. There are so few warm months here. Everything grows fast. It changes by the day. Before long the leaves form a dense canopy, and the air remains heavy with heat and humidity. It is a cacophony of birds and insects.

And just like that, it’s over. Mornings become crisp and fresh. The days get shorter. Branches here and there start to have orange and yellow leaves on them. Then more. Then all of them, and before you realize it the trees are mostly bare, and the trails disappear under a blanket of fallen leaves.

We continue working on the hiking trails, building things, fixing things, preparing for next year, until there’s too much snow on the ground for us to continue. Then we get to work on the cross-country ski trail.

Seeing this process unfold step by step throughout the year in a place as naturally beautiful as the Eastern Townships is a privilege, but you don’t have to work in the forest to enjoy the

benefits of working in nature. Just being outside in nature 2 hours a week can have physical, cognitive, and mental health benefits. 4, 5

All this to say, take a hike! During any season it can be a wonderful experience. Be prepared. Dress in layers, warm socks. The forest is always changing. There is more life around you than you might realize. If you don’t take advantage, you might miss something.

All this to say, take a hike! During any season it can be a wonderful experience. Be prepared. Dress in layers, warm socks. The forest is always changing. There is more life around you than you might realize. If you don’t take advantage, you might miss something.

Bibliography:

- Martinez, L. (2022, February 11).

Where Do Animals Go During Winter in Quebec?

Montreal Science Center

https://www.montrealsciencecentre.com/blog/where-do-animals-go-during-winter-quebec

- Anderson, L. (2023, December 12).

Time for Torpor!

Nature Up North, St. Lawrence University

1. Martinez, L. (2022, February 11).

Where Do Animals Go During Winter in Quebec?

Montreal Science Center

https://www.montrealsciencecentre.com/blog/where-do-animals-go-during-winter-quebec

2. Anderson, L. (2023, December 12).

Time for Torpor!

Nature Up North, St. Lawrence University

3. Martinez, L. (2022, February 11).

Where Do Animals Go During Winter in Quebec?

Montreal Science Center

https://www.montrealsciencecentre.com/blog/where-do-animals-go-during-winter-quebec

4. (2023, May 03).

3 Ways Getting Outside into Nature Helps Improve Your Health

UC Davis Health

5. Swaim, E. (2022, May 28).

8 Health Benefits of Getting Back to Nature and Spending Time Outside

Healthline

https://www.healthline.com/health/health-benefits-of-being-outdoors