Written by Jessica Adams (Nature Nerding)

Reading time: 5-6 minutes

As I was sitting on my balcony one misty morning, enjoying my cup of coffee, my eyes wandered to my garden box in which I had planted some of my favourite fine herbs earlier in the season. My heart sank… ruined. All of them. And the slimy culprits were still there… slowly cruising their way around the box like they owned the place. The more I looked, the more I noticed and my disappointment quickly evolved into curiosity… Slugs. What a peculiar creature. What intrigued me most of all was the fact they don’t seem like an animal that would be likely to thrive… they are slow, soft… seemingly so vulnerable… and yet clearly they do just fine.

I had to admit I knew very little about this oozing invertebrate so omnipresent in our natural world. I remember skimming over the topic in Zoology class back in university, but still had so many unanswered questions and so I figured it was about time I brush up on my gastropod knowledge. Starting with researching the very basics, I was reminded of how very much there is to know when we start studying the wonders of the natural world. Slugs are no exception, as these everyday invertebrates have much more going on than we might care to notice…

What is a slug, really?

While they may appear to share some physical characteristics with worm-type critters, slugs actually fall into the same phylum as octopuses, squids, clams, oysters and snails – that of the mollusks.

As many may guess, a slug is essentially a snail without a shell. That being said, it is not a snail that has lost its shell in the course of its lifetime, but rather over the course of evolutionary time. Interestingly, this has happened along multiple lineages meaning that slugs did not emerge from a single-shelled ancestor but rather emerged independently from various shelled ancestors. This means that while most slugs bear a striking resemblance to one another, they do not necessarily share origins.

Why lose the shell? A shell seems like an awfully good idea if your body is soft, squishy and relatively defenseless. So why bother losing such a seemingly useful protective covering? One theory suggests it is an energy trade-off – foregoing the energetic cost of growing a shell to invest energy in other aspects of survival – such as growing faster in order to reproduce sooner. Another suggests a shell can be problematic when trying to move through tighter spaces which can be extremely useful when attempting to escape danger.

At first glance, a slug’s body might not appear all that elaborate, but when you take the time to observe closely, it truly is fascinating. For starters, as different as they are from humans, slugs do get around “on foot”. Foot being the word used to describe the muscular base of their bodies and the part that contracts and helps move it forward (with the help of mucus, of course). When viewing slugs from above, we can’t help but notice a sort of hump closer to the tentacles – this hump is known as the mantle. The mantle is a feature found in all mollusks and is the area where the visceral mass is located. In some species of slug, the mantle can contain remnants of a shell either in the form of a small plate or granules – evidence of their evolutionary story. Just under the mantle, when it is in use, you can observe an opening called a pneumostome which serves as a breathing pore for the slug – I like to think of it as a single side nostril.

At the head of the body, we can observe two pairs of tentacles. Each pair has different functions. The uppermost can be likened to eyes, though they are only sensitive to light and do not form crisp images like the human eye; they also function as smelling organs. Feeling and tasting are the jobs of the lower pair of tentacles. These sensory tentacles are retractable and can be regrown in the event of a mishap.

Beneath the lower tentacles lies the equipment responsible for wreaking havoc on my fine herbs and so many people’s gardens – the mouthparts. Inside the mouth of a slug, it is almost as if the tongue and teeth are one. The radula, a tongue-like structure, is covered in minuscule serrations known as denticles that rasp off food particles as the slug moseys along at its leisurely pace.

Why so slimy?

A description of a slug’s body would not be complete without giving due attention to mucus (aka slime). If you have ever picked up a slug, intentionally or otherwise, you likely had a sticky residue on your skin afterward. Or perhaps, while walking down a forest path, you noticed glistening trails left behind on the earth. Both constitute evidence of one of the most vital aspects of slug biology: mucus.

Slugs have two varieties of mucus on their bodies helping them in the departments of mobility, communication, and protection. The thin, watery mucus that spreads from the foot out to the edges and from the front of the foot to the back helps the slug get around along with the foot’s muscular contractions. It is in this lighter slime that slugs can pick up what other slugs are “putting down”, so to speak. Whether it be in order to find a mate or for some species of carnivorous, predatory slug to track potential prey. This slime carries messages.

The thicker, stickier mucus coats the remainder of the slug’s body and this not only protects the slug, whose body is mostly made of water, from desiccation, but it can help it slip out of a predator’s grasp. Furthermore, it isn’t very palatable to some animals, serving as an additional deterrent to possible predators.

What is my point?

While doing research, I kept uttering tiny gasps of amazement as I was reacquainting myself with these creatures. And this article touches on but a fraction of their natural history. Admittedly, it’s rare I give them the time of day. I am careful not to tread on them, but it is typically the children with whom I am walking who draw my attention to them…

Present in all different shapes and sizes, unlike a lot of other wildlife, slugs are out in plain sight if the conditions are humid enough. They are just asking to be observed, to be admired for the supernatural-looking beings they are. What’s more, they aren’t going anywhere in a hurry so you can take your time with them, bring the magnifying glass in closer and really get to know them.

These opportunities for intimate observation of and connection with a wild species, no matter the type, are gifts. The next time you come across a slug on your walk through the woods, why not stop and graciously accept this gift, take a moment with this shell-less gastropod… and see what happens? You might be surprised.

Build Your Nature Vocabulary

Use the text and search the web to build your nature vocabulary and try using it the next time you’re out and about in nature, either making observations by yourself or with friends!

- Gastropod

- Phylum

- Foot

- Mantle

- Visceral mass

- Pneumostom

- Tentacles

- Radula

Références

- Slug (New World Encyclopedia)

- Slug (A-Z Animals)

- Slugs of Maryland: Biodiversity and Biology (Aydin Orstan)

- Why Are Snails and Slugs So, Well, Sluggish? (John F. Tooker, Daniel Bliss et Jared Adam)

Photo caption: Though slugs are hermaphroditic, they will attempt to find a mate to reproduce. Once found, they can be observed in a ritual courtship display prior to mating. They each form a circle surrounding their protruding genitalia while sperm is being exchanged. Days later, eggs are laid in a protected area such as a hole in the ground or under a log.

Bu promosyonun en çekici yanlarından biri, bahis severlerin deneme bonusu veren siteler üzerinden yatırım yapmadan oyun oynayabilme rahatlığına kavuşmasıdır. Dolayısıyla, bahis oynamak isteyen ancak bu sitelere para yatırma konusunda tereddüt eden kişiler için deneme bonusları mükemmel bir başlangıç noktası sunar.

When you think of birdwatching, you may be inclined to picture a group of people of a certain age walking slowly along a trail, most wearing a bucket hat and a vest of some sort. As they meander slowly along a trail, they periodically stop, look up to the treetops and lift their trusty binoculars to their eyes, excitedly whispering to their fellow birders about what they are seeing.

When you think of birdwatching, you may be inclined to picture a group of people of a certain age walking slowly along a trail, most wearing a bucket hat and a vest of some sort. As they meander slowly along a trail, they periodically stop, look up to the treetops and lift their trusty binoculars to their eyes, excitedly whispering to their fellow birders about what they are seeing.

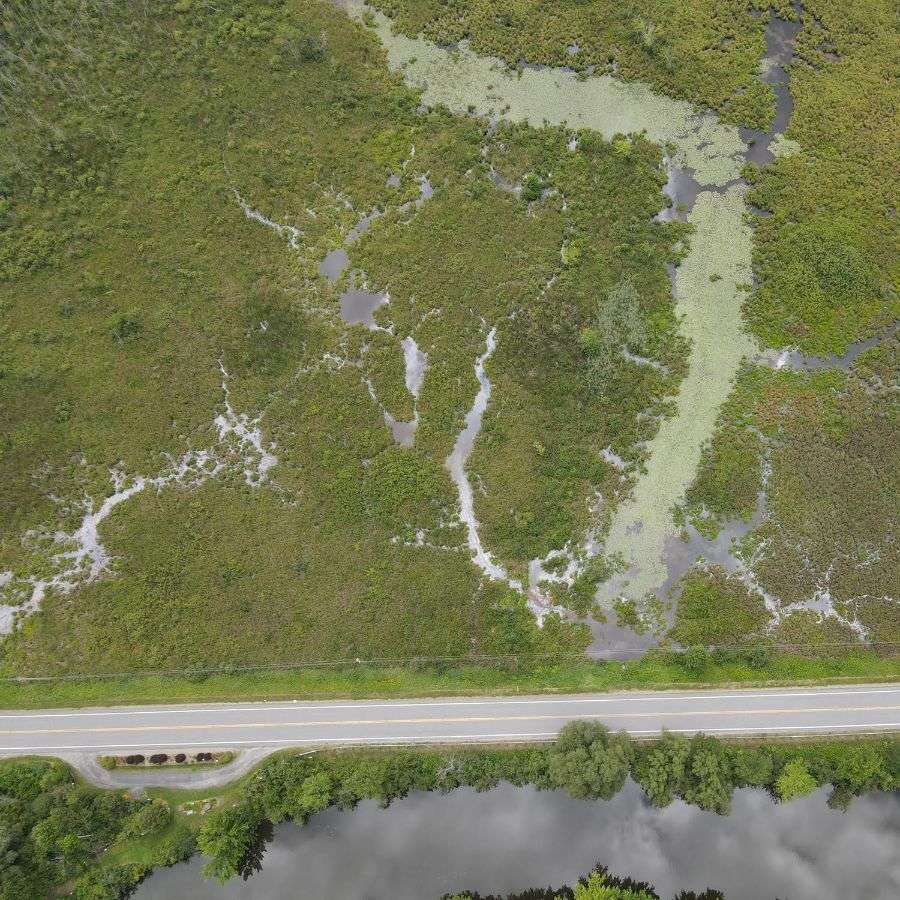

As a child, I remember a certain time of year when the forest would suddenly be full of “ponds”. This was an exciting time as the possibilities for play and exploration were multiplied tenfold! What I did not realize, however, was how important these ephemeral habitats are to the ecosystem.

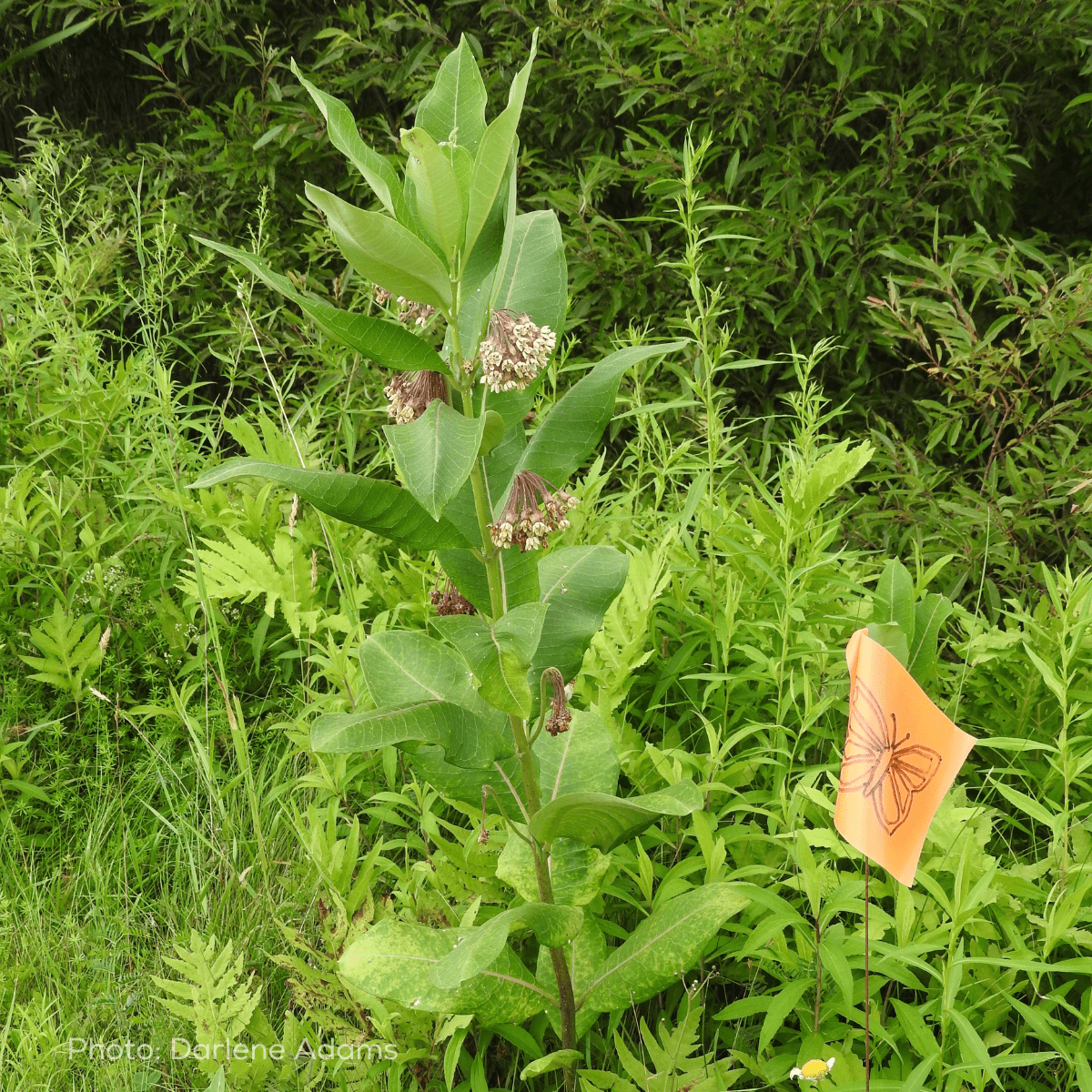

As a child, I remember a certain time of year when the forest would suddenly be full of “ponds”. This was an exciting time as the possibilities for play and exploration were multiplied tenfold! What I did not realize, however, was how important these ephemeral habitats are to the ecosystem. Most flowering plants wait to bloom once the threat of snow has more or less passed, but one of our local flowering plants has other plans. Keen to claim its place in the moister sections of the forest floor, this plant slowly begins to emerge from the still-frozen ground…

Most flowering plants wait to bloom once the threat of snow has more or less passed, but one of our local flowering plants has other plans. Keen to claim its place in the moister sections of the forest floor, this plant slowly begins to emerge from the still-frozen ground…

About the author of this article :

About the author of this article :