Written by Jessica Adams (Nature Nerding)

Reading time: 5-6 minutes

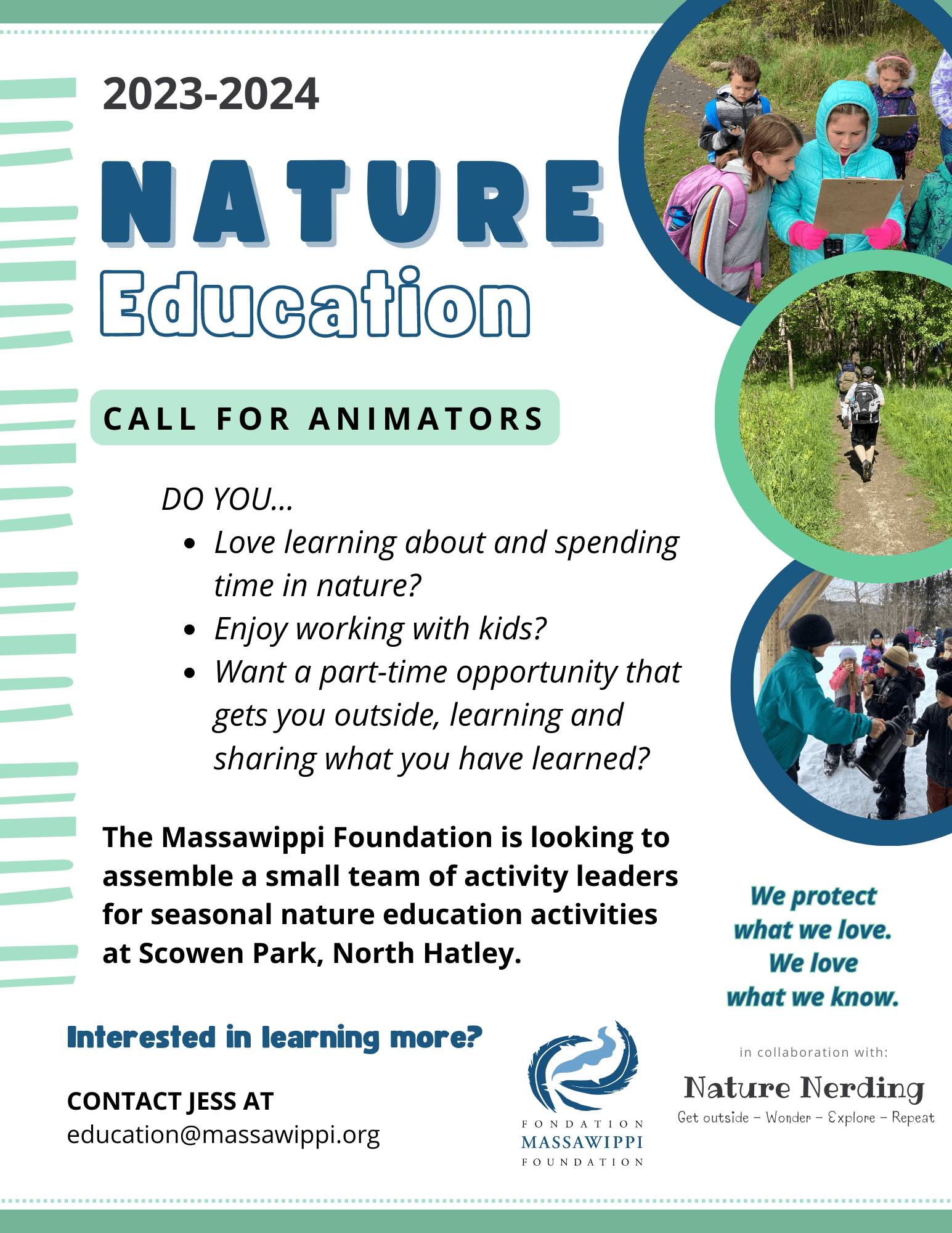

We start every outing of the Massawippi Foundation’s Nature Education Program by gathering around the Scowen Park map. Once we are all huddled in close together, we take the time to say hello, to look back on our outing last season, and to revisit the guidelines to follow for a safe and respectful outing. When it comes to this last part, students proudly chime in with their take on “how to be” as we are walking through the forest. By the winter outing (the second of three throughout the school year), students are pretty clear not only on what the expectations are, but why they exist in the first place.

We make this discussion a priority not to restrict enjoyment, but to expand awareness. The idea is for these children to form an understanding of the part they play in a bigger system of interconnected beings. The message is that their actions matter. The hope is this will encourage new ways of thinking that will stick with them for a lifetime and influence their future interactions with the natural world.

This is the first in a series of articles meant to start a conversation around the principles underlying the guidelines common to so many trail networks. With the number of people enjoying the outdoors on the rise, it is more important than ever to view park guidelines not as limiting regulations, but as opportunities to mitigate our impact and be part of ensuring the natural environments we love so dearly continue to thrive for generations to come.

Part 1: Honouring the Trail

Trails as Pathways for Recreation & Conservation

“One of the main challenges of the planning, design, and management of natural areas is making decisions that will produce the best quality user experience, while protecting the ecological integrity of the resource base.” (Lynn and Brown, 2003)

Trails are one of the main vehicles for encouraging nature-based tourism. People walk and hike through nature for a variety of reasons, not least of which are the physical and mental benefits we experience by moving and breathing outdoors. There is little doubt as to the benefits trails have on their users… but is there potentially a benefit to the natural areas themselves? Indeed there is. The idea of conserving nature might not factor on the list of top priorities if individuals have never had the chance to experience it firsthand. To know something is to develop a love for it and, naturally, a desire to protect it. Trails provide access to natural areas where it might not have been granted otherwise, providing opportunities to build a relationship with the natural world.

Trails are one of the main vehicles for encouraging nature-based tourism. People walk and hike through nature for a variety of reasons, not least of which are the physical and mental benefits we experience by moving and breathing outdoors. There is little doubt as to the benefits trails have on their users… but is there potentially a benefit to the natural areas themselves? Indeed there is. The idea of conserving nature might not factor on the list of top priorities if individuals have never had the chance to experience it firsthand. To know something is to develop a love for it and, naturally, a desire to protect it. Trails provide access to natural areas where it might not have been granted otherwise, providing opportunities to build a relationship with the natural world.

How we enjoy this access to nature, however, can have consequences. If enjoyed in a way that is mindful, having access to nature will not only have a smaller impact on the surrounding ecosystems, but can be a gamechanger when it comes to connecting people with nature and encouraging pro-conservation attitudes. Conversely, if this access is enjoyed in a way that is careless, the impacts on the habitats through which the trails run could be potentially devastating.

The way the pendulum swings is up to every individual who sets foot on a trail. So what does it look like to enjoy a walk in the woods in a way that is mindful?

Trails Built with Intention

A lot that goes into building a trail. When done properly, everything is taken into consideration, from the trajectory it takes through the forest to the types of tools used. Generally, trails are designed to:

- respect the natural area through which they run, meanwhile showcasing some of its most stunning features

- withstand a reasonable amount of wear and tear (from walkers and from the elements)

- keep trail users safe and on-track

In short, trails are built for enjoyment with hiker safety and conservation top of mind.

Sometimes we venture off trail because we want to see something up close, take a shortcut or find a more private lookout point…. As tempting as it might be and as harmless as it might seem, let’s consider the advantages of staying on trail.

By enjoying the trail and keeping to it, we avoid exposing ourselves to additional risks, such as:

- Getting lost. “Wandering off trail is the number one reason, ahead of injury and bad weather, that adult hikers require search and rescue.” (Moye, 2019) Accidentally losing the trail can happen to the best of us, but whether on purpose or not, a stroll off into the forest can last longer than we’d like and potentially evolve into a serious ordeal.

- Sustaining injuries. Trails are carefully built so walkers can get around with less risk of injury. They skirt more challenging and potentially dangerous terrain and have features like steps and boardwalks for areas that are trickier to navigate.

- Rashes or burns. Trails are generally cleared of vegetation which means we are less likely to brush against Stinging Nettle, Poison Ivy or other plants with neat (but unpleasant) defense mechanisms.

- Bites. Ticks don’t hang out in mud or gravel, but they do hang out in tall grass and leaf litter! Staying in the trail keeps them at a more comfortable distance and decreases the chances of one hitching a ride home with us.

Presumably, those of us who favour trail walking do so because of the beautiful environment. By enjoying the trail and keeping to it, we preserve the natural areas around us by:

- Protecting sensitive and vulnerable life. This can range from avoiding stepping on plants to avoiding leaving behind our human smell that might signal danger (and cause undue stress) to critters living in the forest.

- Maintaining the soil’s porosity and resistance to erosion: Untouched soil on the forest floor is protected by layers of plantlife and organic matter and has a certain absorbency when it rains. If the same areas are trampled time and time again, the top layers of the forest floor recede, revealing the soil beneath. With more trampling, this earth is compacted over time. Not only can water no longer be absorbed, but water running over it gradually erodes the surface, washing away soil particles and important nutrients.

- Preserving the habitat integrity: The more traffic an area sees, the less favourable the soil is for new life to anchor in and get growing. Little by little, this can limit plant growth and the diversity of species.

The opening discussion with students can go in a variety of directions, but we always come back to the notion that guidelines don’t exist to take away the fun, but to protect the natural areas we love so much. A reframe, if you will: by not doing something small… we are doing something big. By choosing to stay on the trail we are taking responsibility for our safety and we are actively investing in the health of the places we are visiting. As visitors, we are part of the natural systems, even if for a brief moment, and we get to choose whether our impact is positive or negative. How wonderfully empowering.

Stay tuned for more information on other common guidelines and how they help us protect the natural areas we enjoy.

References

- Hiking Etiquette (National Park Service)

- Why social trails are damaging to provincial parks (Ontario Parks)

- Day hikers are the most vulnerable in survival situations. Here’s why. (Article by Jayme Moye, National Geographic.com)

- Lynn, Natasha A., and Robert D. Brown. “Effects of recreational use impacts on hiking experiences in natural areas.” Landscape and urban planning 64.1-2 (2003): 77-87.

- Ballantyne, Mark, and Catherine Marina Pickering. “Recreational trails as a source of negative impacts on the persistence of keystone species and facilitation.” Journal of Environmental Management 159 (2015): 48-57.

- Liu, Qianqian, et al. “The effect of human trampling activity on a soil microbial community at the urban forest park.” Forests 14.4 (2023): 692.

Who benefits from time spent in nature?

Who benefits from time spent in nature?  What does connecting with nature look like?

What does connecting with nature look like?

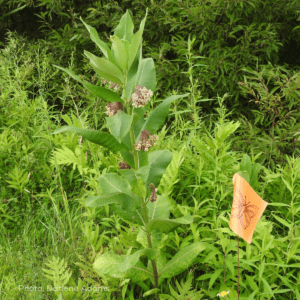

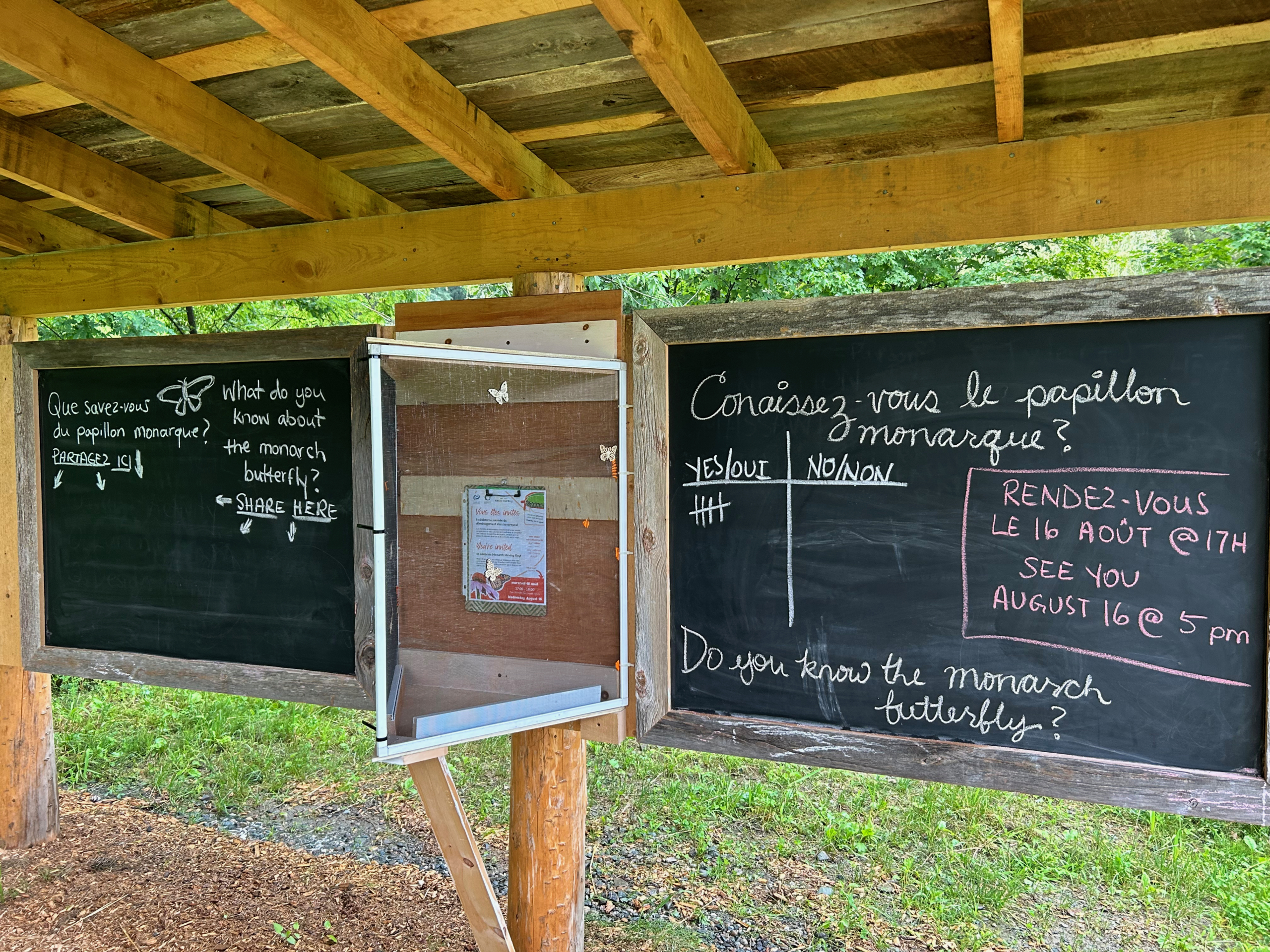

This is a focal point of the project since it is the only plant a Monarch caterpillar will feed on making it essential for Monarch reproduction. Though there are several species of milkweed, the only species present at Scowen is Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). After taking inventory of what Common Milkweed looks, feels, and smells like, we proceeded to mark a handful of data collection sites throughout the fields.

This is a focal point of the project since it is the only plant a Monarch caterpillar will feed on making it essential for Monarch reproduction. Though there are several species of milkweed, the only species present at Scowen is Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). After taking inventory of what Common Milkweed looks, feels, and smells like, we proceeded to mark a handful of data collection sites throughout the fields. Human intervention can be a contentious topic when it comes to conservation efforts. How can we be certain we are doing more good than harm? Are we preventing nature from “taking its course”? These questions can be debated at length and conclusions are typically drawn on a case-by-case basis.

Human intervention can be a contentious topic when it comes to conservation efforts. How can we be certain we are doing more good than harm? Are we preventing nature from “taking its course”? These questions can be debated at length and conclusions are typically drawn on a case-by-case basis.

My birding Walk and Talk at Glen Villa, in the pouring rain on Saturday June 17th.

My birding Walk and Talk at Glen Villa, in the pouring rain on Saturday June 17th.

It’s interesting to note that some of the Massawippi Conservation Trust properties have been included in an extensive long-term monitoring program for stream salamanders. There are currently two studies underway. Indeed, as these properties are free of anthropogenic threats, it is interesting to see the evolution of populations in this sector over a 10-year period. This data can then be compared with sites undergoing significant pressure, such as those under forest management. In addition, the project aims to understand the potential impact of climate change on stream salamander populations. It is possible that climate change will have an impact on stream salamanders, particularly with increasingly frequent and intense dry spells in summer.

It’s interesting to note that some of the Massawippi Conservation Trust properties have been included in an extensive long-term monitoring program for stream salamanders. There are currently two studies underway. Indeed, as these properties are free of anthropogenic threats, it is interesting to see the evolution of populations in this sector over a 10-year period. This data can then be compared with sites undergoing significant pressure, such as those under forest management. In addition, the project aims to understand the potential impact of climate change on stream salamander populations. It is possible that climate change will have an impact on stream salamanders, particularly with increasingly frequent and intense dry spells in summer. This long-term monitoring project stems from a problem often observed in the acquisition of rigorous data for population monitoring, particularly for species with precarious status. Indeed, the lack of funding for knowledge acquisition often results in significant gaps in our knowledge of population trends. The project sponsor, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, has therefore set up a long-term (10-year) monitoring program for the purple salamander throughout the Estrie region. Some ten conservation organizations are involved in the project, including COGESAF. Each organization is responsible for monitoring a small number of streams, thereby reducing project costs and workloads. COGESAF’s role in this project is to monitor two streams on sites designated as “no or low impact” by human activities on the properties of the Massawippi Conservation Trust. As a herpetology enthusiast who has been working as a biologist for COGESAF for the past 5 years, this project is particularly close to my heart. Finally, I’d like to highlight the collaboration of more than a dozen conservation organizations working together to improve knowledge of the purple salamander and protect it more effectively… in the hope that this project will inspire other initiatives like it for other species or other regions!

This long-term monitoring project stems from a problem often observed in the acquisition of rigorous data for population monitoring, particularly for species with precarious status. Indeed, the lack of funding for knowledge acquisition often results in significant gaps in our knowledge of population trends. The project sponsor, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, has therefore set up a long-term (10-year) monitoring program for the purple salamander throughout the Estrie region. Some ten conservation organizations are involved in the project, including COGESAF. Each organization is responsible for monitoring a small number of streams, thereby reducing project costs and workloads. COGESAF’s role in this project is to monitor two streams on sites designated as “no or low impact” by human activities on the properties of the Massawippi Conservation Trust. As a herpetology enthusiast who has been working as a biologist for COGESAF for the past 5 years, this project is particularly close to my heart. Finally, I’d like to highlight the collaboration of more than a dozen conservation organizations working together to improve knowledge of the purple salamander and protect it more effectively… in the hope that this project will inspire other initiatives like it for other species or other regions!