Reflections on Some Common Nature “Do’s and Dont’s”

Part 2: Signs of Human Presence

Written by Jessica Adams (Nature Nerding)

Reading time: 5-6 minutes

The new program for the grade 4 students visiting our trails revolvings around Noticing Signs of Animal Presence. Throughout February and March we had so much fun scouring Scowen Park for clues, investigating and discussing who might have left each clue behind. We were lucky enough to come across tracks, scat, signs of browsing and even some bones, fur and bits of skin left over from a White-Tailed Deer. Each outing served as a reminder that if we pay close enough attention, we can see signs of animals going about their activities all around us, even in the dead of winter.

What happens when animals of the Homo sapiens variety go about their activities in the forest? What types of clues do they leave behind?

In this article we will dive into the “Signs of Human Presence”, considering some of the usual signs left behind by the humans passing through natural areas and some of the not-so-usual signs that have a greater impact than we might realize. This is the second in a series of articles meant to encourage deeper reflection on the principles underlying the guidelines common to so many trail networks (see Part 1 on Respecting the Trail from the March-April newsletter). With the number of people enjoying natural spaces increasing, it is more important than ever to view park guidelines as invitations to participate in reducing our collective impact and hence preserving the natural areas we cherish.

Part 2: Signs of Human Presence

For the Love of Parks

In 2021, Parks Canada and Ontario Parks joined forces in promoting the For the Love of Parks campaign – one meant to “inspire visitors to enjoy (…) amazing places responsibly, for the enjoyment of everyone.” (Parks Canada)

Why do we visit natural areas? Presumably it is because there is something about them that draws us in, that is special and that we love. Why, then, would we make choices that slowly degrade these areas over time?

Oftentimes human actions (unwitting or not) pose a real threat to the ecological integrity of the spaces we frequent. “Ecosystems have integrity when they have their native components intact.” (Parks Canada) Organisations managing natural areas have a responsibility to keep this in mind when it comes to providing access to said areas. The mandate to make these areas accessible should never take precedence over the mandate to protect them. It is therefore everyone’s responsibility to uphold the integrity of these spaces – for the sake of preserving ecosystems and for the sake of preserving our right to access them.

Undesirable Number 1: Good Old Trash

It is heartbreaking and frustrating when we stumble across trash in the middle of a natural area. When we see this somewhere that is special to us… it almost feels personal. In addition to it being offensive and unsightly to other park visitors, it is problematic for wildlife because it doesn’t belong.

Everything in an ecosystem serves a purpose and is able to participate in a relatively balanced energetic exchange with the other components. Whether it be to provide substrate, nutrients or shelter, the role is necessary and the impact is moderated by the other processes going on simultaneously.

Trash is foreign and not only unable to contribute positively to an ecosystem, but can create an important imbalance. Firstly, trash takes a long time to degrade and while doing so, leaches toxins (and zero nutrients) into the soil. Second, various types of waste have the potential to cause needless suffering and even mortality. From empty bags to plastic containers, curious wildlife picking up the scent of food can become trapped and suffocate or starve to death. Other items can easily be mistaken for food and can be ingested, causing choking or other digestive issues that can lead to death. Moreover, whether mistaken for food or not, anything with a sharp edge to it can cause injury to unsuspecting critters, leaving them vulnerable.

Various forms of trash have the potential to take a lot from an ecosystem without giving a single thing in return… but what about the things that can eventually break down? Are they as bad?

The Not-So-Usual Suspects

“But… it’s biodegradable!” I hear this often during our fall post-outing snack when I ask students to chuck their apple cores in a brown paper bag instead of throwing it into the tall grass.

So many of us (myself included) have been taught that biodegradable equals harmless. It wasn’t until well into adulthood that I was able to fully grasp the importance of such a seemingly harmless action. Once again, it comes down to preserving ecosystem integrity. By leaving behind food waste we are indirectly feeding animals which can:

- Be unhealthy for animals. Animals’ systems are made to process the foods that are found naturally in their habitats. Not a granola bar, even if it’s organic.

- Cause animals to get habituated to humans. Animals catch on very quickly and can come to associate humans with food, eventually becoming nuisances as they hang around and beg for food, maybe even becoming aggressive. It’s all fun and cute until raccoons get bold.

- Influence population numbers of one species to the detriment of another. To illustrate by way of an example: one study found that supplemental food significantly impacted Red Squirrel numbers and studies on Bicknell’s Thrush have shown that their nesting success is significantly impacted by Red Squirrel abundance. “In years when red squirrel populations are high, the reproductive success of Bicknell’s Thrush declines.” (Hinterland Who’s Who) Feeding squirrels could kill birds. Who knew?

Leaving behind additional food sources for wildlife creates an imbalance that can inconvenience humans and wildlife alike. Moreover, these ‘compostable items’ degrade far less quickly than we might think (e.g. banana and orange peel can take up to two years to break down in nature). Animals are capable of fending for themselves, our food scraps leave unnecessary extra resources, which can ultimately compromise ecosystem integrity.

Lastly, on the list of “Not-So-Usual Suspects”, we have facial tissue and toilet paper. Tissues often fall into the category of “But… it’s biodegradable!”

But are they and does it matter?

For all the reasons mentioned above, it is not advised to toss tissue paper in the forest and it bears mentioning that contrary to popular belief… it will not dissolve into the soil anytime soon. Actually, if left to do its thing, a tissue left in nature can take anywhere between one and three years to decompose completely! Not to mention it contributes nothing of value to the ecosystem as it does so.

Pack In, Pack Out

It can be easy to fall into the way of thinking that one single action by one single person is “no big deal”. This is when we have to stop and remind ourselves that none of our actions are ever truly isolated. We are part of a vast (and growing) whole. The choices we make have an impact and the more people who decide to make a similar choice, the greater the impact positive or negative.

So what to do with anything that comes into the forest? Treat it all like trash. Treat it like a real threat to the ecosystem’s integrity and bring it back with you. Always have a bag handy in your hiking pack so you can contain the messier things. You can do the sorting (compost, recycling, garbage) when you get home, feeling pleased with yourself that you chose to invest in the future of that beautiful place you just visited. And if you want to be a major investor – feel free to pick up the slack and also commit to removing anything left behind by others (when it’s safe, of course).

We go to these natural spaces because we enjoy them and appreciate them as they are. By choosing to leave nothing behind, to bring it all back out with us, we are actively upholding an ecosystem’s integrity and this is as much a solemn pledge to the natural spaces as it is to ourselves.

References

- Trashed Natural Areas (Leave No Trace)

- Crisis in our national parks: how tourists are loving nature to death (The Guardian)

- “Biodegradable” Food Waste (New Hampshire State Parks)

- Once you know what happens to food you leave outdoors, you’ll stop doing it (Popular Science)

- Ecological Integrity (Parks Canada)

- Wildlife and Litter Don’t Mix (Alberta’s Institute for Wildlife Conservation)

- Imagine if 13 million visitors… (Parks Canada)

- Don’t feed wildlife: It can do more harm than good (BCSPCA)

- Bicknell’s Thrush (Hinterland Who’s Who)

- Klenner, W., & Krebs, C. J. (1991). Red squirrel population dynamics I. The effect of supplemental food on demography. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 961-978.

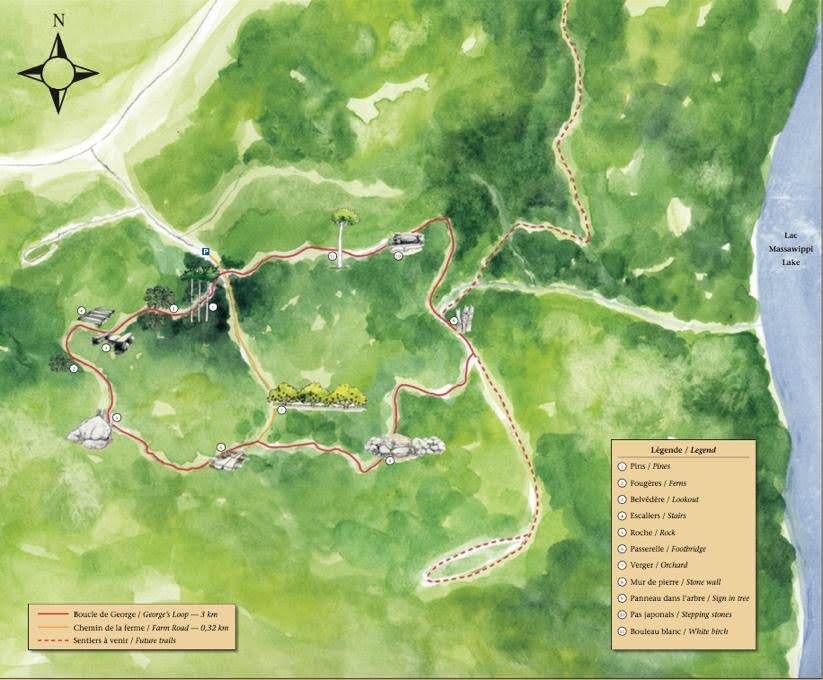

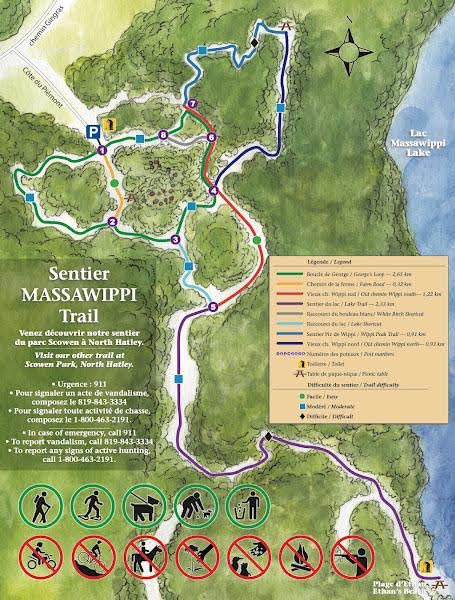

To describe our process more specifically, and anecdotally I suppose, I will tell the story from my perspective of the conceptualization and construction of George’s Loop. This was the first trail to open in the Wardman Sector of the Massawippi Trail. I have included maps, of the trail network then and now, to give an idea of our progress. The map will continue to grow. For those building these trails, the map serves as a diary. It is hard to look at it and not remember the stories associated with it. Here we began, at this turn. There is where we were when the leaves changed. That switchback was when Mahicans had his baby. Here it began to snow and we all stopped working at the same time and looked up to watch it fall.

To describe our process more specifically, and anecdotally I suppose, I will tell the story from my perspective of the conceptualization and construction of George’s Loop. This was the first trail to open in the Wardman Sector of the Massawippi Trail. I have included maps, of the trail network then and now, to give an idea of our progress. The map will continue to grow. For those building these trails, the map serves as a diary. It is hard to look at it and not remember the stories associated with it. Here we began, at this turn. There is where we were when the leaves changed. That switchback was when Mahicans had his baby. Here it began to snow and we all stopped working at the same time and looked up to watch it fall.

In the case of George’s Loop, we had no Point A from which to start on our trek toward Point B. The mandate was simply to make the forest accessible to visitors of all comfort levels in the woods. There are many ways to build a hiking trail, with varying degrees of intervention, from a raised, wide path of stone dust with ditches on both sides and culverts allowing water to pass from one side to the other wherever necessary to prevent trail erosion. The other extreme involves simply clearing obstacles on the surface and walking on the forest floor as is. The first extreme is costly and limits the degree to which hikers feel part of nature when they hike. The second extreme quickly disappears if not used enough, and if used too much becomes a path of muck. The trail is beaten down by walkers as the network of capillary roots giving structure to the ground breaks down. Hikers avoid the lowest, wettest part of the trail in the center and the trail gets wider and wider as the process continues.

In the case of George’s Loop, we had no Point A from which to start on our trek toward Point B. The mandate was simply to make the forest accessible to visitors of all comfort levels in the woods. There are many ways to build a hiking trail, with varying degrees of intervention, from a raised, wide path of stone dust with ditches on both sides and culverts allowing water to pass from one side to the other wherever necessary to prevent trail erosion. The other extreme involves simply clearing obstacles on the surface and walking on the forest floor as is. The first extreme is costly and limits the degree to which hikers feel part of nature when they hike. The second extreme quickly disappears if not used enough, and if used too much becomes a path of muck. The trail is beaten down by walkers as the network of capillary roots giving structure to the ground breaks down. Hikers avoid the lowest, wettest part of the trail in the center and the trail gets wider and wider as the process continues.

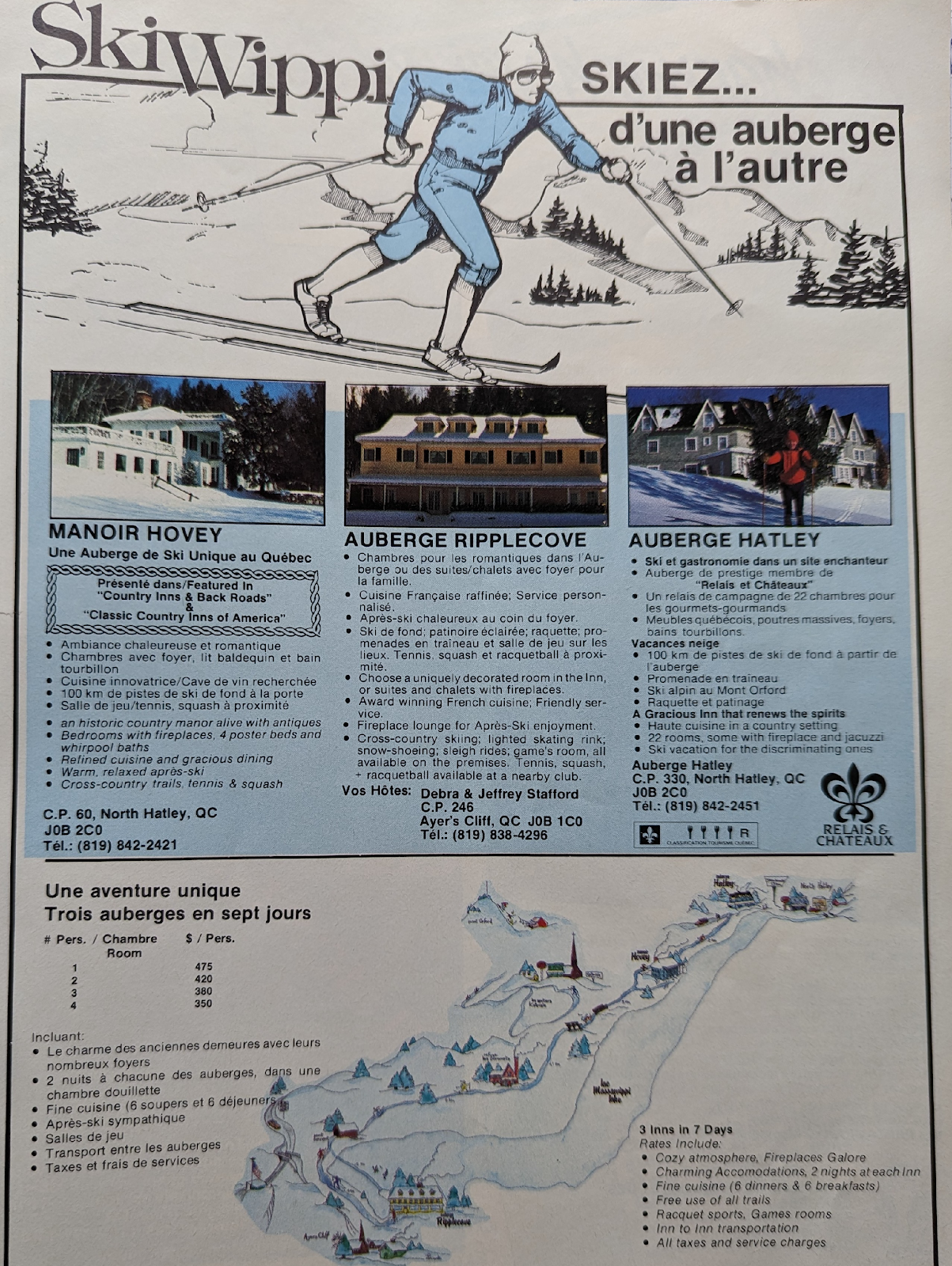

The trail continues down toward what used to be the Skiwippi trail, cutting through a straight, long pile of stones that once served as a fence or property line.

The trail continues down toward what used to be the Skiwippi trail, cutting through a straight, long pile of stones that once served as a fence or property line. It took us over a year to build George’s Loop. It takes about 45 minutes to walk it completely. Hiking gives a person a chance to think and reflect and decompress without the distraction of other people, without constant contact and the demands of our electronic devices. In other moments it allows us to be completely present with those friends and family around us. The land here has had many uses over the years, dating back thousands of years, but whatever it has meant for people living nearby, its importance as a store of carbon and a home for plants and animals remains. We must remember that we are guests in the forest, and strive to act as its protectors as best we can.

It took us over a year to build George’s Loop. It takes about 45 minutes to walk it completely. Hiking gives a person a chance to think and reflect and decompress without the distraction of other people, without constant contact and the demands of our electronic devices. In other moments it allows us to be completely present with those friends and family around us. The land here has had many uses over the years, dating back thousands of years, but whatever it has meant for people living nearby, its importance as a store of carbon and a home for plants and animals remains. We must remember that we are guests in the forest, and strive to act as its protectors as best we can.

Trails are one of the main vehicles for encouraging nature-based tourism. People walk and hike through nature for a variety of reasons, not least of which are the physical and mental benefits we experience by moving and breathing outdoors. There is little doubt as to the benefits trails have on their users… but is there potentially a benefit to the natural areas themselves? Indeed there is. The idea of conserving nature might not factor on the list of top priorities if individuals have never had the chance to experience it firsthand. To know something is to develop a love for it and, naturally, a desire to protect it. Trails provide access to natural areas where it might not have been granted otherwise, providing opportunities to build a relationship with the natural world.

Trails are one of the main vehicles for encouraging nature-based tourism. People walk and hike through nature for a variety of reasons, not least of which are the physical and mental benefits we experience by moving and breathing outdoors. There is little doubt as to the benefits trails have on their users… but is there potentially a benefit to the natural areas themselves? Indeed there is. The idea of conserving nature might not factor on the list of top priorities if individuals have never had the chance to experience it firsthand. To know something is to develop a love for it and, naturally, a desire to protect it. Trails provide access to natural areas where it might not have been granted otherwise, providing opportunities to build a relationship with the natural world.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the site passed through several hands as agriculture and forestry formed the basis of the economy in northern Stanstead Township. In 1854, a sawmill, a blacksmith shop, a bridge and farm buildings were located near the site. Just above the falls, a house was built between 1883 and 1906, accompanied by a barn-stable. Evidence of these human activities have been corroborated by archaeologists.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the site passed through several hands as agriculture and forestry formed the basis of the economy in northern Stanstead Township. In 1854, a sawmill, a blacksmith shop, a bridge and farm buildings were located near the site. Just above the falls, a house was built between 1883 and 1906, accompanied by a barn-stable. Evidence of these human activities have been corroborated by archaeologists. The heritage site is also of interest for its landscape value. The site is marked by the presence of the 55.17 m-high Burroughs Falls, part of the Niger River. The property, which is largely wooded, also features several types of forest stands: cedar, hemlock, maple, and tall pines planted along the access road.

The heritage site is also of interest for its landscape value. The site is marked by the presence of the 55.17 m-high Burroughs Falls, part of the Niger River. The property, which is largely wooded, also features several types of forest stands: cedar, hemlock, maple, and tall pines planted along the access road.

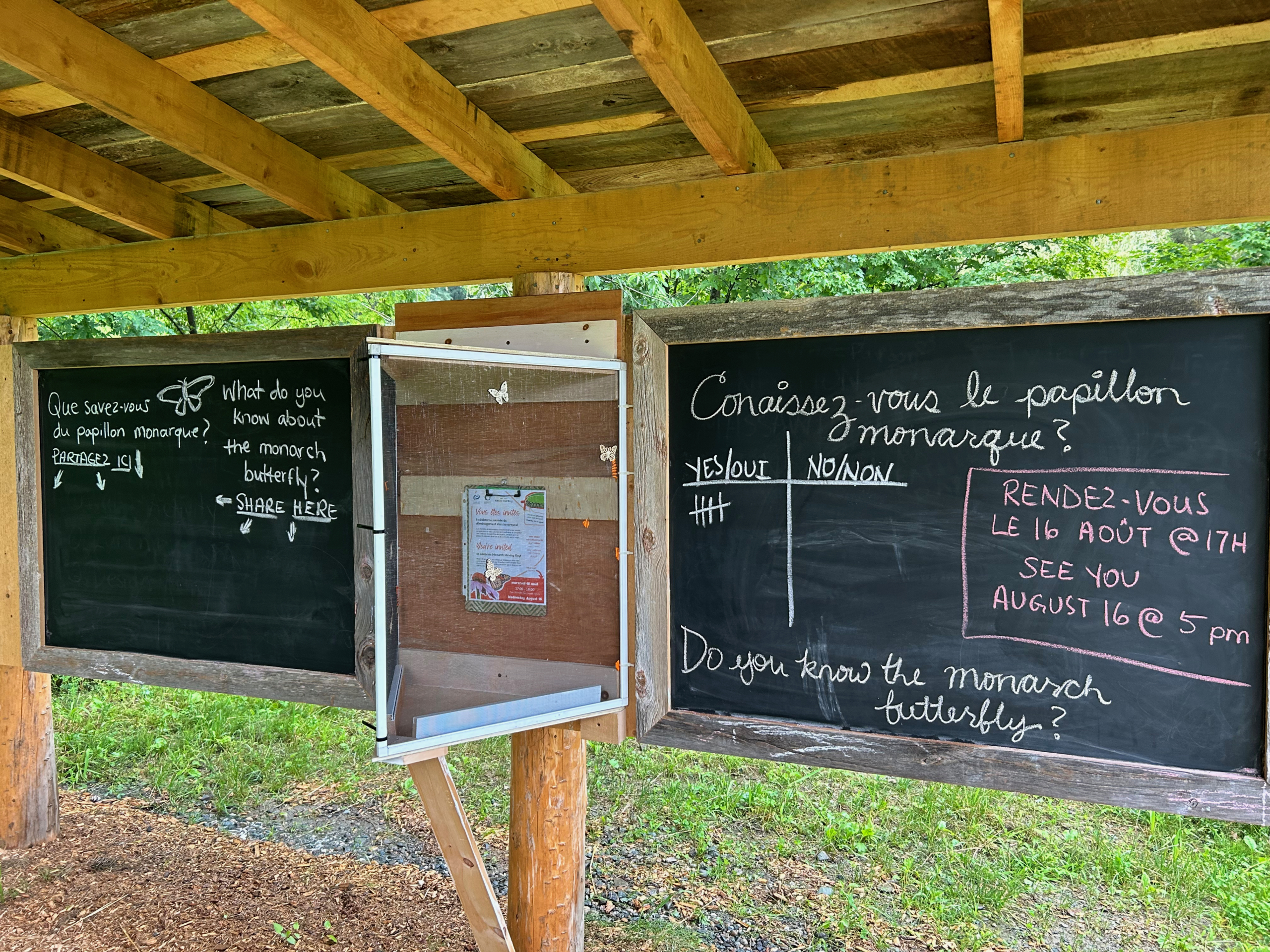

This is a focal point of the project since it is the only plant a Monarch caterpillar will feed on making it essential for Monarch reproduction. Though there are several species of milkweed, the only species present at Scowen is Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). After taking inventory of what Common Milkweed looks, feels, and smells like, we proceeded to mark a handful of data collection sites throughout the fields.

This is a focal point of the project since it is the only plant a Monarch caterpillar will feed on making it essential for Monarch reproduction. Though there are several species of milkweed, the only species present at Scowen is Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). After taking inventory of what Common Milkweed looks, feels, and smells like, we proceeded to mark a handful of data collection sites throughout the fields. Human intervention can be a contentious topic when it comes to conservation efforts. How can we be certain we are doing more good than harm? Are we preventing nature from “taking its course”? These questions can be debated at length and conclusions are typically drawn on a case-by-case basis.

Human intervention can be a contentious topic when it comes to conservation efforts. How can we be certain we are doing more good than harm? Are we preventing nature from “taking its course”? These questions can be debated at length and conclusions are typically drawn on a case-by-case basis.

My birding Walk and Talk at Glen Villa, in the pouring rain on Saturday June 17th.

My birding Walk and Talk at Glen Villa, in the pouring rain on Saturday June 17th.

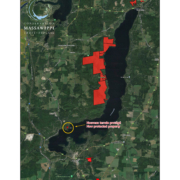

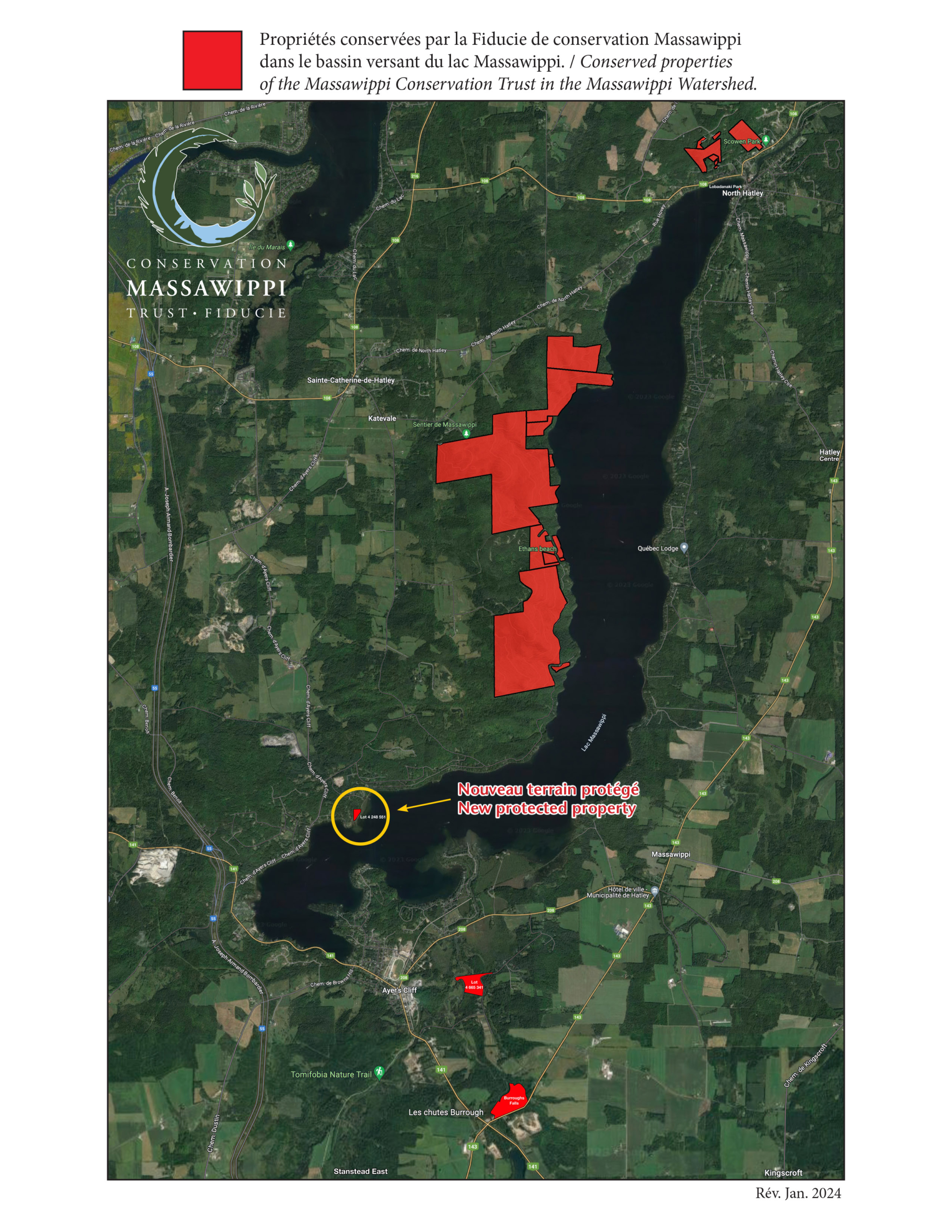

It’s interesting to note that some of the Massawippi Conservation Trust properties have been included in an extensive long-term monitoring program for stream salamanders. There are currently two studies underway. Indeed, as these properties are free of anthropogenic threats, it is interesting to see the evolution of populations in this sector over a 10-year period. This data can then be compared with sites undergoing significant pressure, such as those under forest management. In addition, the project aims to understand the potential impact of climate change on stream salamander populations. It is possible that climate change will have an impact on stream salamanders, particularly with increasingly frequent and intense dry spells in summer.

It’s interesting to note that some of the Massawippi Conservation Trust properties have been included in an extensive long-term monitoring program for stream salamanders. There are currently two studies underway. Indeed, as these properties are free of anthropogenic threats, it is interesting to see the evolution of populations in this sector over a 10-year period. This data can then be compared with sites undergoing significant pressure, such as those under forest management. In addition, the project aims to understand the potential impact of climate change on stream salamander populations. It is possible that climate change will have an impact on stream salamanders, particularly with increasingly frequent and intense dry spells in summer. This long-term monitoring project stems from a problem often observed in the acquisition of rigorous data for population monitoring, particularly for species with precarious status. Indeed, the lack of funding for knowledge acquisition often results in significant gaps in our knowledge of population trends. The project sponsor, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, has therefore set up a long-term (10-year) monitoring program for the purple salamander throughout the Estrie region. Some ten conservation organizations are involved in the project, including COGESAF. Each organization is responsible for monitoring a small number of streams, thereby reducing project costs and workloads. COGESAF’s role in this project is to monitor two streams on sites designated as “no or low impact” by human activities on the properties of the Massawippi Conservation Trust. As a herpetology enthusiast who has been working as a biologist for COGESAF for the past 5 years, this project is particularly close to my heart. Finally, I’d like to highlight the collaboration of more than a dozen conservation organizations working together to improve knowledge of the purple salamander and protect it more effectively… in the hope that this project will inspire other initiatives like it for other species or other regions!

This long-term monitoring project stems from a problem often observed in the acquisition of rigorous data for population monitoring, particularly for species with precarious status. Indeed, the lack of funding for knowledge acquisition often results in significant gaps in our knowledge of population trends. The project sponsor, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, has therefore set up a long-term (10-year) monitoring program for the purple salamander throughout the Estrie region. Some ten conservation organizations are involved in the project, including COGESAF. Each organization is responsible for monitoring a small number of streams, thereby reducing project costs and workloads. COGESAF’s role in this project is to monitor two streams on sites designated as “no or low impact” by human activities on the properties of the Massawippi Conservation Trust. As a herpetology enthusiast who has been working as a biologist for COGESAF for the past 5 years, this project is particularly close to my heart. Finally, I’d like to highlight the collaboration of more than a dozen conservation organizations working together to improve knowledge of the purple salamander and protect it more effectively… in the hope that this project will inspire other initiatives like it for other species or other regions!